The Partido dos Trabalhadores in São Paulo

At the beginning of

October last year the biggest South American metropolis –and the heart

of the Brazilian economy– elected as a mayor Marta Suplicy of the PT (Partido

dos Trabalhadores, the Workers' Party). From the beginning of the

campaign for the second ballot, Suplicy had been the favourite to win,

having polled more than than twice as many votes as her nearest rival

in the first round, when there were more than ten candidates, including

former PT mayor 'hard core' Luiza Erundina. (There is a second ballot

every time there is no candidate with an overall majority in the first,

a play-off between the two most popular first-round candidates.) Yet it was not all

plain sailing. Though Suplicy is widely seen as a 'pink' socialist,

being of patrician extraction and aligned to the 'lighter' version of

the PT, the 'right' were extremely concerned at the prospect of her

election. Moreover, the 'centre' collapsed in disarray. All this meant

that the anti-PT forces managed to scrape together a respectable number

of votes in the second ballot, in spite of the fact that their

candidate was utterly unpopular, being widely seen as a ruthless and

rather blunt representant of elite interests. (He had been reponsive

for building expensive road artwork at the expense of public transport,

and for organising favela removals while building Potemkin

façades masquerading as 'social housing ensembles'; he had also

left the education and health services

in a shambles, even though public debt doubled during his

administration.) This unpopular candidate still managed to poll an

impressive (and somewhat worrying) 41%. This still left

room for a comfortable victory for Marta Suplicy, but it was not quite

the landslide that had been expected. Nevertheless, significantly, and

perhaps more importantly, the PT increased its number of

representatives in the Council by 8 –it now has 17 seats out of a

total of 55. This is a very

significant improvement for a Council long notorious for corruption and

largely in thrall to a small number of big building contractors, estate

developers and bus companies. In what follows I

will try to sum up the possibilities open to Suplicy's administration,

looking at the probable trends in the direction of urban policy, and

the prospects for change in Brazilian society more widely– as well as

raising a number of associated questions along the way. Participation One of the key

issues faced by PT administrations across There have been

some successes --but also some inevitable problems--

in the PT's campaign to increase the participation of citizens

in the administration of their cities. Thus in the case of In addition to the

question of participation, in

The regionalization

programme envisages the transformation of these 'regional'

administrative units into sub-prefectures (boroughs), which will have

more self-government and more resources. This is an old idea that was

very popular during the last (1988-92) PT administration

in São Paulo, when there was even consideration given to the

idea that the 'Regionals' should have elected governing bodies. That

programme was shelved by subsequent right-wing administrations, but is

almost certain that a new attempt to implement it will now be made.

Marta Suplicy certainly did say this when she was a candidate. Democracy: social, liberal or direct? 'Participative

planning' in local governments raises the rather broader issue of democracy itself, and this is made of even

greater interest by the numerous electoral victories of the PT across The name itself, democracy, is a little baffling. For it means the rule of the people, but if the people are in power, over who, or what, could they extend their rule? In fact the word was borrowed from the Greeks by nascent bourgeois society in capitalist economies, and is meant to suggest that all men and women in a democratic society are equal. Since this flies in the face of social practice and everyday experience, liberal ideology –bourgeois social 'theory'– does not say as much, stating only that in a democracy all men and women have the same rights ('all are equal before the law'). And when it comes to the political forms which rule the life of such a society, everyone has the same right to have a say. However, since it is not possible for every member of society express his/her will directly, they elect representatives who speak in their names (and in the name of their interests). This is representative democracy, also known as liberal democracy – in liberal ideology the best (or least bad) available social organization of society. Critiques of representative democracy argue that in practice the interests of less powerful people will always be hijacked by the greater influence of the dominant class, whose interests thus will always ultimately prevail. Lenin went as far as to say that democracy was the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. I tend to agree with this position, but also feel that the alternative known as direct democracy1 is a utopian notion in a bourgeois society – and most probably in any society: one has only to recall the experience of the now extinct 'actually exisitng socialist' societies of Eastern Europe. But before leaving the question of representative/ direct democracies, let us recall a third form of democracy, namely, social democracy. In fact, this is not a 'variant' of the former type. It is a proposition that was born amid the transformations that took place in capitalist society during the last part of the nineteenth century. At the time, after centuries of rapid, even spectacular, growth, which had seen the world-wide spread of capitalism –the period of extensive accumulation–, there was suddenly no room for more expansion and the Great Depression set in which lasted twenty years (1875-95). This was the time when ideas about social democracy began to be discussed, at the beginning of the transition to a new stage of capitalism. During the twentieth century, especially after the second world war, it became clear that the new forms of capitalism which were developing were nothing like 'classical' capitalism of the industrial revolution or the Victorian Age. One important change was that there was now definitely no new room for expansion –the whole world had already been conquered by wage labour and commodity production. This meant that any increase in commodity production could only proceed through an increase of the productivity of labour. This was, in fact, a new stage of capitalism, called the stage of intensive accumulation, or, for short, the intensive stage. One of the crucial things about this intensive stage –which is that of contemporary capitalism– is the crucial role of techniques and technical progress, which are the sole source of growth (and therefore, of profit). As a result, the level of subsistence of workers is greatly increased: more health, more education, more leisure, a better urban environment, all are necessary to operate the increasingly sophisticated productive processes and provide an equally increasing variety of services in the greatly reduced working day. This is the material basis of the welfare state –according to the empirical taste of the British– and of the more explicit political form –as espoused by the Germans– of social democracy. Social democracy is one the most controversial propositions for social practice in capitalism, and it has already been debated for over a century, starting with Kautsky's arguments with Engels, and later with Luxemburg and Lenin. Ultimately, the question comes down to this: can there be socialism, or some socialism, in capitalism? In theoretical terms there can hardly be an affirmative answer to this, but the spectacular rise of subsistence levels at the centres of world capitalism made many people feel that theoretical discussion was irrelevant and academic – what mattered was that most people lived much better than before, and this could be construed as some measure of socialism. And it may well

turn out that these questions are academic for another reason: if

social democracy is a political form consistent with the intensive

stage of capitalism, and if this stage is now drawing to its end.

Production is well on its way to become fully automatised – in a

process which has been rather loosely referred to as

de-industrialisation. This means that society will no longer be

organized, as it is now, on the basis of, and around the production of

commodities for profit. This is not the place to conjecture about a

society in which manufactured goods are in abundance, and people go

about performing services and spending leisure time. But surely such a

society will not any more be organised on the basis of

commodity production or wage labour; so, in other words, it will not be

a capitalist society any more. Thus the long-term prospect for social

democracy is that it will vanish with capitalism itself. However we at

the periphery leave such questions to those at the centre to wonder

about. It is time to return to the present and immediate future, which

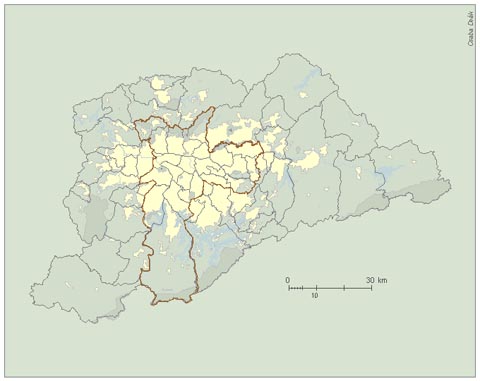

is still part of the era of social democracy – or in the case of The local versus central Both democracy and participation ('participative planning') are key issues in the relationship between local units or regions and the greater whole to which they belong. This is even more true in São Paulo, because of the administrative mess it is in: none of the three levels of government (municipal, state, federal) coincides with the metropoltan area, which is smaller than the state but bigger than the municipality; and the Metropolitan entity which was created thirty years ago, specifcally to deal with this problem, was seriously weakened after only ten years, to a point of hardly existing at all except on paper. As well as antagonisms created by class divides, or even by mere clash of interest groups, there are antagonisms which stem from the sheer scale of both space and society itself. For example, at the national level we have such a clash in the conflict between the national need to build a dam for a power plant and the local people whose life it would disrupt. The same clashes occur in the city – let's think only of the simple cases of building roads and airports or preserving the basin of a water reservoir. Of course there is always the possibility of 'compensation', its size being the result of the balance of forces between the locals and the greater whole (the nation, the city). But the point is that both the need for the course of action and the amount of 'compensation' will be decided at the level of central planning; there is little choice left for the local community, apart from the decision on whether to comply willingly or unwillingly. Which says a lot on the possibilies for local autonomy. On the other hand

there are issues that are clearly best resolved at the local level. This is the case for most of land use

planning and building regulation, and also for the administration of

local infrastructure and services (such as street maintenance, water

supply and sewage, and even the basics of

education and health service). In fact, such issues can

not really be resolved at the central level, for this would require

an unthinkable level of data/ intelligence gathering at the centre

simply to get to grips with the local situation, let alone to

deliberate and take all the necessary decisions. This was one of the practical problems of centrally

planned 'existing socialism' in post-war The great question,

of course, is how to find the right level of centralization: to avoid

creating a momentum towards excessive centralisation: but equally, to

ensure that the pendulum does not swing too far in the other direction

which could result in anarchy.Unfortunately there are hardly any

theoretical answers to such questions, so that these have to be found

in social practice. One lesson that can

be learned is the danger that can be posed to local bodies by national

interests in direct conflict with the local community. The

administrative bodies of local communities –perhaps precisely because

of the greater degree of participation allowed– are often to the left

of central governments (recall the famous red towns of Democracy in an elite society Whatever lessons in

democracy

Thus, to the extent

that the Partido dos Trabalhadores follows de facto, if

not necessarily in words, the social democratic credo, the future of

its administrations in São Paulo and elsewhere across the

country is likely to be problematic. And it will be more so if they do

keep to a left trajectory. It is also worth remembering that, a decade

ago, PT mayor Luisa Erundina (now in the Socialist Party) presided over

what, without a shadow of doubt, was one of

the best administrations ever in São Paulo, but she was

subjected to such a barrage of scorn –or else silence– in the major

newspapers and other media that it all but neutralized the political

effects of her achievements. Furthermore, the growing political

strength of the Workers' Party, which makes the election of a PT

President in 2002 a concrete

possibility, has already led to the preparation of countermeasures, in

an attempt to ensure that such a president will wield less power than

their more reliable predecessors. One such measure is a mooted increase

in the independence of the central bank, which is currently under the

direct command of the Executive. In fact this has been discussed for

years, but now rumours are becoming more persistent about the

preparations for making the central bank solely responsible for

decision-making on a range of important financial questions, including

interest rate. The plan is to make it sufficiently independent to be

able to produce a recession or, as the case may be, a way out

of one– irrespective of the government in office. It would be no

surprise to see such measures to pass into law

by October or November 2002 – that's last

minute before elections… And there may well be similar measures, such

as the fixing by law of monetary and inflationary targets, and

budget deficits, or the signing of international commitments within Mercosul

or Alca (Nafta) or yet even with the IMF. It is even possible,

although less likely, that such measures will be written into the

Constitution –as was the case with the peso/dollar parity in However, the

reproduction of elite society is not unproblematic, of course; nor is

such a society free from antagonisms. In particular, as the balance of

payments problems continue –largely caused by indiscriminate import of

consumption, and especially of capital goods– it becomes ever more

difficult not to allow home-based production to develop. This

will mean that the old structures of elite superprivilege, and the

archaic power relations which support them, will come under increasing

strain, challenged by developing productive forces seeking further and

unhindered development. One possible interpretation of the spread of

the PT, and the party's victories in the most recent by-elections, is

that new forces and organisational forms –which look more

'bourgeois-like'– are emerging in what is now an almost wholly

urbanized society. (A very serious caveat to this, however, is

that although the strength of capital in manufactures and services has

greatly increased at the expense of those in agriculture, there has

been no corresponding increase in the strength of a

Brazilian bourgeoisie at the expense of the old-style elite (coronelato).

This is because a substantial part of this increased capital is under

foreign control, and thus does not give rise to corresponding social

forces in For what are the

great problems of the metropolis? Certainly there is extreme income

concentration, unemployment and misery, but these affect the country as

a whole; they are not particular to urban agglomerations. The main

problem in relation to spatial organization –which can be considered as

an 'urban' problem– is the precarious provision of infrastructure

items. Although this also can be seen as symptomatic of a national

Brazilian problem –the habit of constantly justifying the

weakening of the productive structures by the refrain 'poor country,

poor infrastructure', as referred to earlier–, it also has specifically

urban components, such as the lack of a rapid transport system –

building on the underground system in São Paulo stopped eleven

years ago and when work started again it did so, unbelieveably, on an

unconnected stretch of about 8 kilometres, way

out in the periphery, more than 25 km away from the

centre. This was instead of what was the obvious priority, a 'fourth

line' going towards the South West of the city, through the high income

districts and along the 'new centres'…

Another

infrastructural problem for the city

is the urgent need for cleaning up the environment, and to at long last

tackle the management of water supply. And not least, there is the need

to address issues of land use regulation and policy – the virtual

absence of these currently gives a free hand to petty favour brokers

and big speculators alike. Then there is the need for a serious attempt

at building a public revenue basis to provide for the foregoing...

As regards the immediate plans of the PT government in São Paulo: it will definitely take concrete steps towards participative budgeting; it will increase the autonomy of sub-municipal administrative bodies ('regionals'); it will increase investment in public transport rather than in road structures – although it is unlikely to be able to make a clear-cut decision on the Underground, and instead will remain bogged down with ideas (corridors, terminals, vans, minibuses, other extravagant variants) for improvements to the hopelessly saturated bus system; it will go some way towards overcoming both the general recourse to the scarcity refrain and the particular policy of concentrating investment in the high income south-west sector; and it will certainly increase investment in basic health and education. It will also probably try to lessen the extremely regressive nature of property taxes, and perhaps even to set up the long-debated policy of minimum income (broadly equivalent to unemployment benefit), although it is doubtful how much it will be able to achieve on these scores. There is nothing certain about the outcome of such plans; and these thoughts about the electoral gains of the Workers' Party raise perhaps more doubts than they dispel. We may not be at the threshold of socialism. But there still is cause for celebration. This writer certainly did celebrate on election day and toasted the new mayor and her allies with friends. At the very least, they thought, we all will breathe slightly cleaner air for some time to come. References 1

As put forward by Antonio

Negri; see for instance his critique of Bobbio's apology of

liberal democracy in Capital &

Class 37, pp.156-61. |