São Paulo

In Carmona, Marisa & Burgess, Rod (orgs, 2001) Strategic planning & urban projects/ Responses to globalisation from 15 cities Delft University Press, Deft, pp:173-82 (text) & 282-88 (illustrations)

. .

|

|

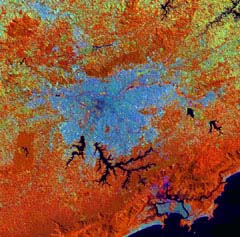

Figure 1 Satellite photograph of São Paulo (Landsat, 1998) |

|

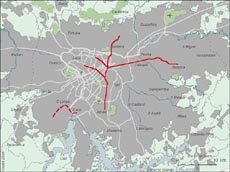

Figure 2 Migration of the town centre (`top locations', in red) towards southwest. |

|

Pic 1 The march towards southwest: view over Pinheiros River looking north. |

|

|

|

|

Pic 2 Low density detached houses are being gradually replaced by high-rise buildings of flats. |

City Profile

São Paulo is the largest urban agglomeration in South America, with a population of 18 million people. It lies at 800m above sea level and at 60 kms from the coast. The climate is more temperate than in neighbouring (400km) Rio de Janeiro, which lies at the same latitude but at sea level on the coast. The built area of 200.000ha is spread out from the original centre in a large octopus shape with a 70km East-West axis and a 50km North-South axis (see Figure 1). The main mass of urbanisation is bordered in the south by two artificial water reservoirs and a steep slope where the plateau falls to sea level and by a mountain range in the North. This means that most of the urbanizable land for expansion lies in the east and west.

The urban form is radio-concentric with more radial than tangential elements. High-income groups have traditionally occupied the South-western sector (in blue in the drawing of Figure 2). As the city grew the city centre started drifting South-west, as though following the high-income population. The march towards the southwest occurred in a leapfrogging fashion leaving wide gaps in- between. The first leap, about three km long, occurred in the late Fifties when São Paulo had 4 million people. Banks, office buildings, smart shops and services occupied the central ridge and formed the Avenida Paulista. Fifteen years later there was a second leapfrog of five kilometres when office buildings, bank branches and the first Shopping Centre were set up on newly opened Av. Faria Lima. Nowadays there is a shift of new office headquarters further south still to Av. Berrini --some 15 km. from the old centre. São Paulo's centre today (in red) is something like a comet with a tail stretched out towards the south-west.

The South-western sector concentrates most of the economic activities except manufactures and most of the residential income. The sector consists of a 15 to 20kms long equilateral triangle in which infrastructure provision is of a high standard, the quality of the environment is fair and accessibility reasonable. Originally residential settlements consisted of low density detached houses but high rise apartment blocks are now being built at rates twice as fast as housing and they already make up one third of the built stock in dwellings (Table 1 and Figure 4). The other sectors and the outer periphery consist of predominantly middle and working class residences, and they are the location of the bulk of manufacturing industry. This originally located along the railway (after 1850) and after 1950 along the roads. Here the conditions of the infrastructure and environmental quality are bad and often extremely bad.

Worst still are conditions in the favelas. These settlements were formed by invasion after the mid-Seventies on generally public land and today favela dwellers make up about 15% of the urban population of the Metropolitan area -- some two and half million people. The roots of such extreme differences both in income and the quality of the environment go back to the origins of São Paulo and Brazilian society itself.

|

|

Pic 3 Trianon Park: A quiet corner off Paulista Ave. |

|

|

|

|

MAP 1 Região Metropolitana de São Paulo, 1881-1995: growth of urbanized area From its original site on a hilltop São Paulo grew to its current size of 18 mn people living on a 200 000ha (2000 sq.km) urbanized area. |

City History

The economic heart of modern Brazil

São Paulo is the largest South American metropolis, but it is also the youngest. Rio de Janeiro became the capital of the Portuguese colony in 1763 because of its coastal location and proximity to the mining region of Minas Gerais. Buenos Aires, in its turn, became capital of the new-born Vice-Kingdom of the River Plate by about the the same time (1776), reflecting its growing economic weight at the expense of Lima. In contrast, as late as 1850 São Paulo was still a small borough of hardly 15.000 people. Indeed, up to then it had been little more than a jumping board for the 'bandeiras', slave hunting expeditions or military campaigns in the struggle against Spain for the south-western border regions. But 1850 was also the year of the suspension of the African slave trade and also of the promulgation of the Land Laws, which instituted private property in land. In practical terms this set the conditions for the introduction of wage labour and capitalism in Brazil, about three decades after the Declaration of Independence (1822). With wage labour and capitalism came industrialisation and urbanisation and a period of high rates of accumulation and rapid growth, similar to that experienced in England in the eighteenth century. São Paulo was to become the centre of this process. A peculiarity of the Brazilian society is that although wage labour predominates, it is not bourgeois society. At Independence, there was no revolution and replacement of the colonial elite by a capitalist class (the bourgeoisie). On the contrary, Independence was merely a process by which the colonial elite set up a state apparatus of its own. The transfer of part of the national surplus to the overseas metropolis continued but now as part of a process of hindered accumulation. Here the transfer of the surplus now took the form of interest payments, profit remittances, unfavourable terms of trade and freight and insurance payments.

São Paulo became the main economic centre of the Brazilian economy with the introduction of the coffee economy in the region in the mid-nineteenth century. For more than half a century coffee was the main export staple of Brazil and São Paulo was at the heart of the coffee region. During the the same period rapid industrialisation and urbanisation made São Paulo the major industrial city in the country. When the world crisis of 1929 put an end to the 'coffee cycle', the leading position of São Paulo in the Brazilian economy had already been firmly established. The ensuing balance of trade constraints made it necessary to broaden industrial production and to supply the rapidly increasing home market at least with consumption goods. The dynamism of São Paulo now became based on manufacturing rather than on an ephemeral export staple.

By the end of the 1970s and after a decade of exceptionally rapid growth -- which had been dubbed the `Brazilian economic miracle'--, Brazil already had the seventh largest national product in the world with a diverse structure of manufactures dominated by car production. The share of São Paulo of national manufacturing GDP amounted to over 42% and half of this was concentrated in the Metropolitan Region itself.

.

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

| Built floorspace, total

São Paulo Metropolitan (est.) 500 000 000 sqm São Paulo City 329 000 000 sqm |

||||||

|

|

||||||

Such economic developments induced an urban process which started with a century of extremely rapid growth. Between 1870-1970 São Paulo grew from a small town of 23,000 people to become a major metropolis of over 8 million people (see Map 1 above). Part of these people came from other regions of the country, but immigration from abroad made significant contributions and today São Paulo is a multi-ethnic city with over a million-strong Italian, Portuguese, German and Japanese originated groups and over a dozen lesser groups from Europe and Asia still strong enough to have their own restaurants, food and book shops and even neighbourhoods.

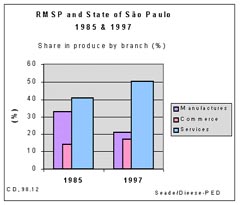

After this period the pattern of urbanization took a sharp turn and since then the São Paulo Metropolitan Region has been dominated by two trends. First, its galloping growth rate fell to an almost vegetative level with a drastic slow-down in the rural-urban migration intake (see Figure 3 and Map 2).It still grew of course and today it is an agglomeration of some 18 million people - but with growth rates approximating vegetative levels the forecasts are that it will not reach much over 23 million people by 2020. Secondly São Paulo made a transition from being a predominantly industrial region to being a major commercial, financial and services centre. Such trends reflect broader trends at the national level: in consequence of a fall in demographic growth rate coupled with an already high level of urbanisation (80% in 2000 and 98% in the State of São Paulo), the process of migration from rural to urban areas has slowed down and the period of high rates of urban growth is over. On the other hand, manufacturing is losing share in GDP nationwide at the expense of finance and services.

Within the State of São Paulo, in turn,

the metropolitan region concentrates the bulk of all branches of industry

except agriculture. Furthermore, in spite of an hypothetical and muchdebated

process of `decentralization', a decline in its share in national manufacturing

-- a declining portion of both national and São Paulo State GDP

-- is more than offset by an increase in São Paulo's share in the

São Paulo State's product in the tertiary: trade and services industry

(Figure 4).

|

Figure 4 RMSP and State of São Paulo, 1985 & 1997- If the metropolitan region has been losing some of its share in the State's produce in manufactures (violet), it also has been increasing its share in both commerce (red) and services industry (blue) in the period 1985-97. |

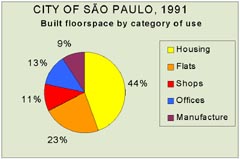

Accordingly, the fastest growing portions of built stock are for office buildings and retail shops, along with high rise residential blocks according to a tendency to more intensive land use (Table_1; for the share of each use, see graph of Figure 5 below).

Table 1

Built floorspace, by type

City of São Paulo, 1986-91

| Building type |

% of total

|

Growth rate

|

| . |

(1991)

|

(% p.a)

|

| Houses |

42.7

|

1,5

|

| Flats |

26.2

|

5,4

|

| Offices |

11.4

|

4,6

|

| Shops |

8.9

|

4,2

|

| Manufactures |

10.7

|

1,0

|

| Total |

100,0

|

2,8

|

|

Figure 5 City of São Paulo , 1991- Built floorpace according to building type. |

In this way there a shift from emphasis on rapid growth and industrialisation to consolidation and expansion of services. Greater São Paulo undergoes an incipient process of deindustrialization and tertiarization demanding a whole range of new needs from the reskilling of the labour force to a major adjustment of the physical infrastructure and public services.

Indeed, the main question São Paulo faces

today relates to the quality of urban infrastructure and the environment:

How can the Metropolitan Region move from a period of rapid growth and

chronic infrastructure shortages to a stage of consolidation, in which

the quality of urban life becomes a central concern?

|

|

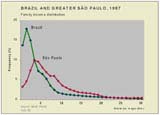

| Figure 6: BRAZIL and RMSP, 1997: Family income distribution. -Distribution curve on a base of 1 Mw (minimum wage), which in 1997 was worth R$ 120., or about US$ 100.-. Average household income: US$ 1200.- monthly (1997). |

|

|

| Map 3 RMSP, 1990: The urban structure The major structures in transportation are a few expressways (thick lines) and a mere 45km long Metrô (underground) network (dotted), pictured on the map left. As a result, the urban agglomeration is fragmented into a number of relatively isolated portions as shown earler on the sketch of drawing 1 |

|

|

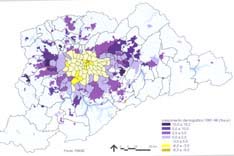

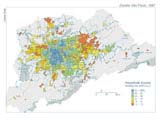

| Map 4 RMSP, 1997 Spatial distribution of residents' income -There is a clear predominance of higher incomes in the southwestern sector _where are also the areas best attended in infrastructure. Medium incomes occupy a consolidated core, whereas low income population spreads out in the periphery. |

|

|

Pic 7 New office buildings along Pinheiros River. |

3

Globalisation, Opportunities and Contradictions

The metropolis of an elite society

For all its dynamism and status as the centre

of Brazilian economy, São Paulo of course still makes part of Brazilian

society, with all its contradictions of a colonially-rooted elite society,

plus the problems of contemporary capitalism. The latter requires urgent

reorganisation of the productive forces (the reorientation of `economic

regulation') away from mass production, which leads to overproduction and

unemployment, towards new principles of regulation. It also needs an antidote

to the anarchy of the market without too much or too far-reaching State

intervention. The former --the elite society-- adds to these problems by

imposing a permanent break on development, resulting in lower per capita

income and a very high income concentration in the São Paulo Metropolitan

Region though not as high as that of Brazil

(Figure 6), one of the

world's highest. Among the effects of this pattern of development at the

level of the urban agglomeration is a kind of reproduction of scarcity,

which is manifested in acute shortages of infrastructure (Map 3). This

leads to marked spatial differentiation over the metropolitan area, as

reflected, for example, in the spatial segregation of the population according

to income ( Map 4).Thus in enormous tracts of urban space huge contingents

of poor people live in poor quality dwellings in poor urban environments,

in sharp contrast to the enclaves of smart housing, proud office buildings

and haughty company headquarters. The contrast between destitute poverty

and ostensive wealth is so great in fact, that it has prompted some to

talk of `dual development' or the `dual city'. These terms are misleading

though, since both sides of the `duality' are the result of one and the

same process. To take a very recent example: the recession implemented

after a frustrated moratorium on foreign debt (1986) inaugurated what was

to become a second `lost decade' and real wages declined by 40% between

1989 and 1996 while unemployment increased from 9,1% to 15,1% over the

same period. The effects of this economic policy were quickly manifested

in São Paulo: there was a doubling of the number of favela dwellers

to over two million people who, along with another three million in illegal

and precarious settlements, lead an uneasy coexistence with the hyper-modern

`intelligent' office buildings and company headquarters, which multiplied

in the same period (Picture 5 a and b).

..b. ..b. |

|

| Pic 5 'Dual city', where poverty and opulence coexist uneasily. | Pic 6 Unemployment promts many to try to eke out a living as street vendors at busy corners of the city |

Such contradictions notwithstanding, São Paulo has consolidated its economic and financial primacy within Mercosul. It concentrates the greatest number of finance banks and foreign company regional headquarters, it boasts the highest volumes of daily trade in Latin American stock exchanges and is becoming the most attractive city for business and leisure tourism (as measured in number of visitors) in the region..

The slowing down of growth rates has also lead

to a rather unexpected result over the last two decades: spatial segregation

of the population according to income, although still high, did decrease

in the period between 1977 and 1997 (Maps

of Figure 7 below).

|

|

| Figure 7: São Paulo Metropolitan Region, 1977 & 87: Spatial segregation according to income.- Negative segregation (exclusion, blue-green) and positive segregation (yelow-brown). Both negative and positive segregation show a marked decrease in the period, due mainly to the fall in the rate of demographic growth of the urban agglomeration. |

In fact, spatial differentiation did become, and is becoming, less pronounced with the fall in the migration rates and the less rapid growth of the periphery. Since there was no change in the policy of provision of urban infrastructure during this period, this shows the potential for urban improvement and an eventual transition to the intensive stage of accumulation, based on a new emphasis on qualitative growth indexes such as per capita income, technological levels and the quality of the environment.

The latest trends and the challenge

Because of São Paulo's position as the main economic centre of both Brazil and Mercosul, the city tends to show the fastest reactions to shifts in economic conditions and policies home and abroad. Two distinct effects can be observed in its urban structure. First, it benefits from more public investment in infrastructure and private investment induced by the former; it boasts the highest proportion of the national skilled labour force, it has experienced a sizeable expansion of advanced technology and world market-oriented urban activities, and has many of the local branches of sophisticated international firms. Second, it is also the locus of social antagonisms which become ever more obvious given its greater projection as a world city. These include social injustice, precarious urban infrastructure, unemployment and informality, urban violence and favela settlements. These will remain until Brazilian society is transformed from an archaic elite society based on permanently hindered accumulation to a more egalitarian society allowing for a full development of its productive forces and providing its urban agglomerations with infrastructure at new quantitative and qualitative thresholds (Figure 8). That is a challenge, however, not for only São Paulo but for the country, if not the Latin American continent, as a whole.

One of the crucial elements of the life of any metropolis is of course planned State intervention. The planning process in São Paulo has gone through many different stages over the last five decades. There was a first stage of no formal or explicit plan at all. But this was also the time when in the early twenties the first large-scale urban transportation system was built by the Anglo-Canadian São Paulo Light and Power Co, which was awarded the tram concession by the city council. The building of this network allowed the extension of the urbanised areas beyond the three kilometre radius, to which the city had been hitherto been confined. Interestingly enough, the first urban plan worthy of the name, the Plano de Avenidas of Prestes Maia (an engineer who later became Mayor of São Paulo in the early 40's), had the dubious merit of reversing the previous policy by emphasising private rather than public transport, and cars rather than the rail. This plan envisaged the canalisation and rectification of the three main rivers and the building of a set of Avenidas. It also postponed the building of an underground network in favour of private cars and public buses. In the period from the sixties to mid-seventies, development or integrated plans became popular in Brazil. None of them was more comprehensive, large-scale and ambitious than the PUB- The Basic Urban Plan, elaborated in 1968 by a gigantic consortium Asplan/Daily/Montreal commissioned by Gegran (Executive Group for Greater São Paulo). PUB had the specific purpose of dealing with the spatial organisation of Greater São Paulo as the urban agglomeration was now outgrowing the administrative limits of the City of São Paulo.

The PUB envisaged 650 km of Metro lines, 650 km of express ways, and the transformation from a monocentric urban to a polynucleated metropolitan structure supporting 42 million people by the year 2000 (Figure 9). It was the time of the `Brazilian miracle' already mentioned and expectations about the future were running high. However, the PUB was just too big for São Paulo and it remains today little more than a reminder of the heyday of large-scale integrated plans in Brazil - for more than a decade, from the mid-60s to the mid-70s there was government support and finance for all medium and big cities to make master' or development' plans. By the end-Seventies the economic boom petered out, however. Only two of the proposals in PUB were partially realised - 80 kms of expressways were built and construction of the Metrô started according to a dramatically reduced target network merely 65kms long. But the urban structure proposals came to nothing and the town centre started its unplanned drift towards the south-west and then south, and urban sprawl continued in the highly inefficient pattern of leapfrogging and incorporation of large areas of unused space. The building of the Underground went at such a slow pace (barely 2 km a year) that the gap between demand and the service offered kept widening rather than starting to narrow. When urban growth slowed down and there was a real chance of closing the gap, building halted altogether in 1989 when the network was 45 km long and all plans were shelved. It was not to start again until 1996 on a 10 km stretch in the periphery --unbelievably-- unconnected to the existing lines, not part of any plan but with World Bank finance (Figure 10). Planning resumed only in 1998 with the start of a new comprehensive transport plan which will be described further below.

It was not just in São Paulo, of course, that the plans were not implemented. Lack of implementation and the slow down in economic growth by the late70s led to the formulation of sectoral plans related to selected aspects of the urban structure, such as sewerage, water management, transport or urban renewal. The half-institutionalised Metropolitan Authority -- the Gegran-- never became an elected body, such as the Greater London Council for example and it was renamed Emplasa and became a half-forgotten body within the administrative structure of São Paulo State. Its swan song was the 1993 Integrated Metropolitan Development Plan. This included a masterful Chapter on three Scenarios for SãoPaulo based on different estimates of the future levels of economic and social development in Brazil, but virtually no proposition at all, since Emplasa had no powers to make any. The jurisdictions of administrative structures, such as municipal boundaries (Map 5), and the regionally structured bodies like the water and sewerage (Sabesp), power supply (Eletropaulo) and telecommunications authorities (Telesp), overlap and none correspond to the effective urban area. Consequently the sectoral plans and projects have remained largely being implemented in isolation from each other and most frequently deal with only a part of the agglomeration.

In the early Nineties a new period in planning began under the aegis of neo-liberalism, which in practice meant cutbacks in public expenditure and the sale of public assets to private companies (`privatisation'). Urban services are less easily privatised than other public assets. These included: mines (Vale do Rio Doce), steel plants (Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional), the State of São Paulo telecommunications system (Telesp, sold in 1998 to Telefonica of Spain), electric power distribution (Eletropaulo became Elektropaulo, sold to a multinational consortium of foreign firms), and some busy stretches of interstate trunk roads. In contrast, water and sewerage supply and urban transportation have not been privatised although there has been talk about that as well so that it remains an open question. Generally speaking there is a strong rhetoric about diminishing the inefficient State' which reinforces the arsenal of excuses for non-investment in urban structures and services. More than that, since 1992 IMF loan contracts include a clause according to which public investment is `expenditure' as though it yielded no return and thus it increases budget deficit, which in turn is to be kept within narrow limits…

One of the problems hardest to face is that of popular housing. The National Housing Bank that for some twenty years had channelled resouces for house building programmes with varying degrees of success, was extinct in 1988 and since then there is no nation-wide programme for housing provision. This is not easily provided at the local level since housing is more of an economic rather than an urban (in the sense of spatial) problem as is attested by the fact that `favelisation' in São Paulo is a new process and came with the two lost decades already referred to. By the early seventies there was virtually no favela settlement in São Paulo, but in 1987 there were already over 800 000 favela dwellers, a number that rose to almost two million (1 900 000) by 1993. Thus the attempts of the municpality to alleviate the problem were not spectacular successes due in the first place to the sheer scale of it (Figure 11). In fact the main focus of `social' housing provision became addressing the problem of favelas, either by upgrading or by removal, according to the politcal position of the municipal government. A Workers'Party 1989-92 administration urbanised (which means building of drainage, sewer, water and electricity distribution systems and some remodelling of the motley settlement of houses -- see Figure 12) little less than 30 000 units _ perhaps 10% of all favelas; whereas a subsequent right-wing government launched a much-publicised `Cingapura project' (Figure 13) and cleared about 8000 shacks and re-located the people in flats in five and eleven-storey buildings (`vertical favelas'), which was not even 2% of all favela settlements.

In spite of such hostile environment, and after almost a decade of near-paralysis the late Nineties saw the re-birth of initiatives on the part of various government bodies dealing with the São Paulo Metropolitan Region, spurred perhaps by the near-calamitous state of most of the urban services, illustrated in the table below by ever longer traffic bottlenecks.

Table 1

Greater São Paulo, 1992-6

Length of traffic

bottlenecks in rush hours

(km)

_________________________________

| Year |

Morning

|

Evening

|

| 1992 |

28

|

39

|

| 1993 |

37

|

54

|

| 1994 |

66

|

96

|

| 1995 |

67

|

98

|

| 1996 |

80

|

122

|

| 1997 |

65

|

109

|

| 1998 |

66

|

103

|

| 1999 |

67

|

115

|

| 2000 |

72

|

117

|

| 2001 |

85

|

116

|

| 2002* |

108

|

124

|

Source: CET -Companhia de Engenharia de Tráfego, 1998. This table was updated on-line in 2002 to show the effect of traffic restriction in peak ohurs (one-fifth of all cars forbidden in central area) introduced in 1997.

*Value for 2002 is average in March only.

Currently some significant projects at the

metropolitan scale are being realised. They include: a long overdue long-term

transport plan with an emphasis on rapid mass transport ;

a comprehensive initiative for water management that takes into account

resource conservation, drainage and flood control, the treatment of sewerage

and the use of the protected area of the southern reservoirs for leisure

and recreation and other compatible uses; administrative decentralisation

with increased local autonomy and participative budgeting; and a large

scale initiative for the renovation of decayed central areas and the restoration

of historical buildings. These projects are briefly summarised below.

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Urban Projects

Public Transport System

One of the largest and most important projects

currently underway is a complete replanning of the public transport system

to achieve entirely new levels of performance in terms of capacity and

levels of service. Aimed at the time-horizon of 2020, the new transport

plan dubbed PITU 2020 (Integrated Plan of Urban Transport) encompasses

all transport modes and it refers to the whole of the Metropolitan Area.

The Plan falls under the jurisdiction of a specific Secretary of the São

Paulo State government (which also runs the Metrô). This plan fixed

a target of greatly expanding all the main elements of the mass transport

system over the next twenty years. Its main proposals are:

| - extend the existing 49 km long Metrô

network to over 170 kms,

- the 30 km long suburban rail lines to 100 kms, - build 95km of light train track to operate in the periphery, and - a special monorail link to connect both the

new and old airports to the city centre and the Metro network in fifteen

minutes.

|

An analysis of three alternative geometries led to the choice of a broadly extended network (Map of Figure 14) able to become the backbone of the public transport system for the metropolitan region (complemented of course with lighter means such as suburban rail, bus and minivans) .The system would provide coverage to the main sub-centres and to huge extensions of the currently poorly-connected eastern and northern regions. There may soon be news of a new management and financial structure for the implementation of PITU 2020. Hitherto the Underground system has been wholly in the hands of São Paulo State through a Company set up for this end in 1968. There have been several proposals to attract private enterprises to take part in the implementation of the new plan. Such alternatives are still on the drawing board, and the Metro Company itself will have to adapt to the new operational schemes.

The main feature of the programme for the improvement

of the road network is the building of a long overdue Ring Road at a radius

of roughly 40km around São Paulo (Map of Figure

15) which will bring some order into the rather

erratic expansion of the urbanised area exclusively along radial axes.

It will also help to keep heavy freight traffic out of the more central

parts of the city, and make tangential movements in the periphery easier.

Recovery of the Old Centre

Equally important is a programme for the recovery of the old centre of the city, after three decades of slow decay brought on by the shift of the dynamic centre to the south-west. The new transport system would restore accessibility to the town centre, the historic buildings will be refurbished and optical fibres, and telephone and telecommunications infrastructure will be greatly expanded. A centrally located railway station (Estação Júlio Prestes) has already been refurbished as a concert hall and major cultural centre. Private investment will of course play its part and already there is talk of building a near-500m high tower in an old district near the old centre. The process of recovery is expected to trigger further developments. Many non-governamental associations take part together with the local authorities in the effort of tracing a programme for the Centre and implementing it. They gathered in two rather different minded broader associations: Viva o Centro is led by a bank (Bankboston) and composed mainly of retail shops, restaurants, hotels and offices is more entreprise-oriented, aims at gentrification and is less tolerant with street vendors and squatters, whereas the Centrovivo groups popular associations and is more keen on directing subsidies to social housing and generally to prevent the simple cleaning of the centre through exclusion of the diverse froms of marginalism. Both associations agree in that one of the key issues in the requalification of downtown São Paulo is ensuring that residential settlements are not expelled by too high rents which had resulted in bleak and deserted streets in huge tracts of it after opening hours.

The Environmental Billings Project

Prominent among the environmental projects is the Billings Project, which deals with the bigger of the two southern water reservoir systems, and its companion water management project for the entire basin of the São Paulo Metropolitan Region. This seeks to integrate the needs of water supply and treatment, drainage and flood control, power generation, urban settlement and the preservation of the environment. After many decades of debate about the best way to preserve natural resources against urban encroachment, there is growing consensus that the best way to preserve water quality in the water basins is to restrict uses to leisure, theme parks and low-density but high quality settlement that are compatible with this goal rather than to leave them as green areas. This has made these areas vulnerable to invasion by illegal settlements with no sanitation infrastructure at all.The new model s of course demands among other things improved accessibility both by public transport and road, both envisaged by the PITU 2020 and the Ring Road projects respectively. These projects will make the great scenic beauty of the lakes available to the public and thereby provide a shield against further deterioration.

Local autonomy and participative budgeting

One of the key issues Workers'Party (PT) administrations across Brazil elect as such is the question of popular participation in the administration and planning of the city. The southern capital city of Porto Alegre, after three successive (PT) administrations leads in this field. The depth of this participation, as measured by the portion of the budget in the allocation of which communities had a say in some form, may amount to about 3 to 5% of the total budget. This is not much, but it is not to belittle either if one recalls that current expenses, such as running cost of public services, civil servants' pay and service on debt is at least 70% and not unfrequently closer to 100%, depending mainly on the level of indebtedness of the municipality. This leaves at most 30% of the budget liable to decisions regarding in what to invest, but of these also there is always a part already earmarked for some previously decided particular purpose. In this light, then, 3-5% appears as quite significant. More significant yet if we take into account the effect of the decision process itself, the formation of discussion groups in all sorts of (civic) associations and the feeling of participation that this induces in the people taking part in it. Again, however, this can easily be construed as demagogy if we think that fixing a bit more of the pavement in front of Jones' rather than Smiths' doesn't make any real difference for social development.

Be that as it may (see also![]() ),

coupled with participative budgeting, in São Paulo there will likely

be another major initiative called `regionalization', according to which

local autonomy of the 28 administrative units or `regional' districts'

into which the city of São Paulo is divided (refer to

Map

5 of administrative boundaries above)

will be greatly increased. The concrete benefits of such measure will materialise

after some time of actual practice, to be assessed in the future.

),

coupled with participative budgeting, in São Paulo there will likely

be another major initiative called `regionalization', according to which

local autonomy of the 28 administrative units or `regional' districts'

into which the city of São Paulo is divided (refer to

Map

5 of administrative boundaries above)

will be greatly increased. The concrete benefits of such measure will materialise

after some time of actual practice, to be assessed in the future.

Another administrative measure, this one at the national level, makes new instruments of planning and land use control available to the urban administrations. This is the new Statute of the City recently approved by the national congress. Among other measures, the Statute transformed a number of planning concepts into concrete intruments of control, such as the social function of private property in land, a basis for expropriation, zones of social concern, for facilitating lowincome settlements, and progressive property tax --both according to time of idleness and to increasing value-- a powerful means of taxation and induction of more efficient land use.

Fight against pollution

Even though there is no specific plan to reduce

air pollution, a set of measures is currently being planned to deal with

it. Pollution levels are currently running so high that people will accept

a one day ban on driving their cars a week (based on licence plates). The

expansion of the Metro system is expected to help a lot in reducing pollution

and congestion. There are also plans to enforce stricter-emission standards

for new cars and there is also a lobby for a government subsidy for replacement

of old by new cars (the lobby is of course from the car industry).

6

Prospects

Such projects --among others--, if implemented, apart from bringing new levels of urban infrastructure and services, would also signal that Brazilian society is finally ready for a far-reaching change to its historic pattern of development. In fact, it would correspond to the optimistic scenario of the Emplasa plan PMDI 93 referred to earlier. Public expenditure would be put on a footing consistent with the potential status of São Paulo as world-city. Schooling, higher education and public health levels would be upgraded to ensure the formation a skilled workforce needed to keep up with the requirements of technical progress in manufacturing, hi- tech infrastructure and telecommunications, research and development and in a widening range of services and expanding leisure time.

In short, it would mean that the development potential of the most developed part of South America, the core of Mercosul, has a good chance of being realised. It is worth reiterating that the biggest metropolitan agglomerations of the region — São Paulo, Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro— will certainly compete for the position of being the main centre of development and prestige, within Mercosul, a position which will rise or fall depending on the development of the region as a whole (Fig. 16).

There is an analogy here with what is happening, albeit at a very different scale, with Amsterdam and Rotterdam, potential contenders for the position of world-city of north-western Europe. Whereas both will keep up their bid for primacy, they can not lose sight of the fact that it is only together - with The Hague, Utrecht and the other towns in the same region - that they really stand a chance to become the great metropolis of the Rijnmond.

On both sides of the Equator the turn of the century

brings new challenges to late capitalist societies which are now largely

concentrated in urban agglomerations. These will have to produce an answer

to the changes brought about by the latest social developments: total urbanization,

but now with deindustrialisation; the problem of exclusion/participation

which entails the need for reappraisal of socialdemocracy as a privileged

political form of social organization; incomeconcentrating neoliberal policies

unsustainable in the long run; damage to the environment which bring the

limits to growth to the forefront; the increase of leisure time which poses

undreamt-of questions both to everyday life and social organization; and

many others now still brewing, to come to light in the future. São

Paulo will have to take part in the effort to facing up to these challenges.

References

Aglietta, Michel (1976) A theory of capitalist regulation New Left Books, London, 1979

Deák, Csaba (1988) "The crisis of hindered accumulation in Brazil/ and questions of urban policy" Proceedings, BISS 10/ Bartlett International Summer School Mexico, September 1988

Fernandes, Florestan (1972) "Classes sociais na América Latina" in Fernandes (1972) Capitalismo dependente e classes sociais na América latina Zahar, São Paulo, 1973

Plans and government publications:

EMPLASA (1993) Plano Metropolitano de Desenvolvimento Integrado- PMDI 93, São Paulo

GEGRAN (1968) Plano Urbanístico Básico- PUB, São Paulo

MAIA, Prestes (1940) Plano de Avenidas, São Paulo

SEMPLA City Planning Secretariat (1992) Base de Dados para Planejamento, São Paulo

STM-State Secretariat for Metropolitan

Transport (1999) PITU 2020

Plano Integrado de Transportes

Urbanos, São Paulo

Websites:

http://www.vivaocentro.org.br/

http://www.forumcentrovivo.hpg.ig.com.br

http://www.emplasa.sp.gov.br/

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Yvonne Mautner for comments on an earlier version of this chapter and to Sueli Schiffer for help with the organization of data.

Credits

All illustrations of the Author, unless otherwise indicated

Photographs: thanks to

Gal Oppido (2000)

São

Paulo 2000 São Paulo Imagemdata, São Paulo, with kind

permission

Vivian Valli

Anna Deák

Yvonne Mautner

Secretaria do Transporte Metropolitano

.

.