|

|

4 The metropolis of an

elite society

For all its dynamism and status as the centre

of Brazilian economy, São Paulo of course still makes part of Brazilian

society, which has conserved its character rooted in colonial times. Thus

it is not immune to the plagues of an elite society, on top of those ‘normal’

problems of contemporary capitalism. Indeed, the latter is in bad need

of reorganization of the productive forces (reorientation of 'economic

regulation') away from mass production which led to overproduction and

unemployment towards new imperatives or principles of regulation; and it

also needs an antidote against the anarchy of the market without impairing

its supremacy through too much or too far-reaching State intervention.

But, on top of such problems, in the elite society there is a permanent

brake on development, imposed as a manner of continuing colonial-type production,

and resulting in hindered accumulation, a specific form of capitalist

production referred to earlier. One of the concrete results of this is

lower per capita income and what is worse, very high income concentration

even in the São Paulo Metropolitan Region and yet higher nationwide

(Figure 6), one of the word’s highest. Among the effects of such

pattern of development at the level of the urban agglomeration is a kind

of reproduction of scarcity, which materializes in acute shortage

of infrastructure (>> Map 2) and leads to consequently marked spatial

differentiation over the metropolitan area, as reflected, for example,

in the spatial segregation of the population according to income (>> Map

6, but see also a further mention to this below).

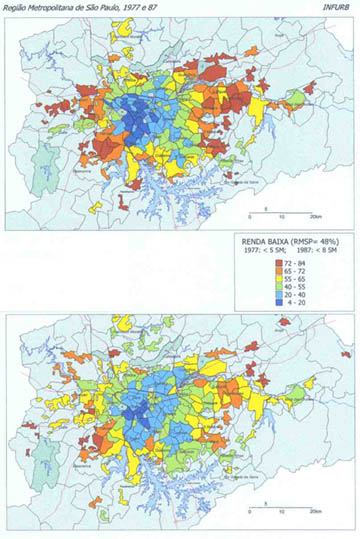

Income distributionThus in huge tracts of the urban space huge contingents of poor status people live in poor quality dwellings in poor urban environment, in sharp contrast with enclaves of smart housing, proud office buildings and haughty company headquarters. The contrast between destitute poverty and ostensive wealth is so great in fact, that it prompted to the coining of such terms as ‘dual development’ or ‘dual city’. They arre rather misnomers, however, since both sides of the ‘duality’ are the result of one and the same process. To take a very recent example: the recession implemented after a frustrated moratorium on foreign debt (1986) inaugurated what was to become a second ‘lost decade’ and wages were down 40% (from 1989 to 96) while unemployment was up from 9,1% to 15,1% (in same period). The effects of such economic policy were quick to show on the urban scene of São Paulo: they materialized in an almost doubling of the numbers of favela dwellers to over two million people who lead an uneasy coexistence with the hyper-modern ‘intelligent’ office buildings and company headquarters, which multiplied in the same period.

- Figure 6: BRAZIL and RMSP, 1997: Family income distribution. -Distribution curve on a base of 1 Mw (minimum wage), which in 1997 was worth R$ 120.-, or about US$ 100.-. Average household income: US$ 1200.- monthly (1997).

Such contradictions notwithstanding, São

Paulo has consolidated, meanwhile, its economic and financial primacy within

Mercosul. It concentrates the greatest number of finance banks and foreign

companies’ regional headquarters, boasts the highest volumes of daily trade

among Latin American stock exchanges and is becoming the most attractive

city for business and leisure tourism (as measured in number of visitors)

within Mercosul.

The slowing down of growth rates also

lead to a rather unexpected result over the last two decades: spatial segregation

of the population according to income, although still high, did decrease

in the period between 1977 and 1987 (Figure 4) and then again in

the next decade. In fact, spatial differentiation did become, and is becoming,

less pronounced with the fall of the migration rates and consequently,

of the less rapid growth of the periphery. Since there was no change in

the policy of provision of urban infrastructure during this period, this

shows the potential for the improvement of urban conditions in the perspective

of an eventual transition to the intensive stage of accumulation,

with the fall of quantitative growth rates (such as demographic or of wealth

production) and a new emphasis on qualitative growth indexes such

as per capita income, technological level and quality of the environment.

|

|